As a few commenters have noted, George MacDonald often used the potentially lucrative serial story form of publication, in which a novella or novel would appear chapter by chapter in the 19th century equivalent of a television season. Serial stories were immensely popular, and, like modern television seasons, could later be repackaged into novels to allow authors to cash in on the works a second time. But 19th century authors had another advantage: they could revise the publication slightly before it was issued in novel form—just like a director’s cut—allowing them to claim to be offering a new version.

I mention this now because The Day Boy and the Night Girl, MacDonald’s next fairy tale, still exists in both formats on Gutenberg.org, allowing a comparison between the two formats. Not that that much was changed, but those interested in Victorian narrative formats might well want to take a look.

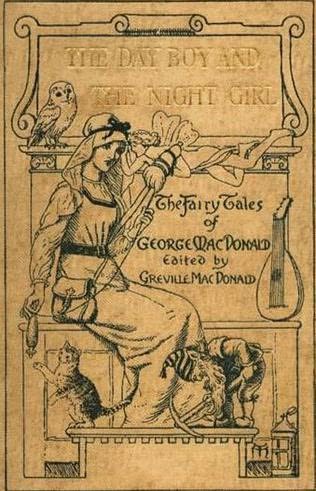

And for once, the serial story did not lead MacDonald into any of his ongoing digressions or bad poetry: The Day Boy and the Night Girl was to be one of his most beautiful works, a genuine fairy tale classic that deserves to be better known.

A witch named Watho, consumed by curiosity, comes up with a plan: to raise one child with no knowledge of night, and a second child with no knowledge of the day. And by no knowledge of night, Watho means no knowledge of darkness whatsoever: she even trains the poor child, named Photogen, to avoid shadows, and he is always, but always, asleep during the entire night. The second child, a girl named Nycteris, lives in a dark tomb, with nothing but a dim lamp for light. She is taught music, but little else, and knows nothing of the day.

(I always wondered how this had been accomplished. MacDonald mentions “training,” which is all well and good, but even the most sound sleepers will occasionally wake up at night, and children often have nightmares or earaches or fevers or whatever. Perhaps she used drugs. I don’t know.)

But Photogen is not merely lacking knowledge of the night; his upbringing has also stripped him from fear. And oddly, Nycteris, for all that she has been kept in darkness, does not know it very well: whenever she awakes, she sees a lamp—the only light she has ever known, a light that fascinates her.

One horrible night, Nycteris awakes to find herself in utter darkness, since the lamp has died out. She panics. Fortunately, a firefly appears. Not unreasonably, Nycteris assumes the firefly will lead her back to the lamp. Instead it leads her to the one thing she truly desires: space. Outside, in the night, beneath the moon and stars.

This is a beautiful scene, filled with wonder and starlight. And at about this time, Photogen is told something of the night. It excites his curiosity, and as I noted, he has no fear, so he decides to try the forbidden and stay out after dark—a dark that finally brings out his fears.

Naturally, this is when the two meet.

Equally naturally, the conversation does not go initially all that well—partly because Nycteris has no idea that Photogen is a boy, or that this is the night, not the day, leading to some major communication difficulties, and partly Photogen is terrified—an emotion he has never had to endure before. (This does, however, lead to a nice bit where Nycteris assures Photogen that girls are never afraid without reason, which of course explains why Photogen can’t be a girl.) Nycteris agrees to watch over him through the night. When day arrives, it is her turn to be terrified. Photogen, not one of the world’s more unselfish creatures, takes off, glorying in the sun.

To be sure, Photogen is, to put it kindly, more than a bit annoying. But he does have the ability to realize his screw-ups, and apologize. And as I’ve already mentioned, the plot, even for a fairy tale, requires a rather large suspension of disbelief. But MacDonald also manages to move beyond some of the conventions of both fairy tales and Victorian literature.

First, intentionally or not, his witch is not motivated by evil, but rather, by curiosity. And her approach, if cruel, is remarkably scientific: she literally sets up an experiment, with controls. I have a vision of her planning to present a nice paper, with footnotes, at the next Conference of Evil Witchcraft. And until the end of the tale, she does very little magic (other than whatever she’s doing to get those children to sleep through the night and the day), turning her more into an Evil Scientist than Witch.

This leads to one of MacDonald’s more interesting reversals: an argument against knowledge. For all of her ignorance—Nycteris has taught herself to read, but has only had access to a few books, and literally cannot tell the difference between the sun and moon—she, not the educated Photogen, is the wiser one, the better equipped to handle the unknown. Photogen’s education actually works against him here. MacDonald is not against the gaining of knowledge—Nycteris’ discovery of the stars and wind and grass is presented as a positive moment. But MacDonald is sounding a cautious note against a dependence upon education, and a considerably less subtle argument about the dangers of experimentation, since the witch’s scientific studies, beyond their ethical issues, also nearly get both Photogen and Nycteris killed.

This note of caution, struck in the midst of an ongoing technological explosion, is odd, but perhaps not entirely unexpected in an era where some worried about the rapid pace of scientific progress. If MacDonald is not precisely urging scientists to step out of their labs, he is certainly noting that scientific knowledge and methodology, if applied without ethics, can lead to evil places indeed. That may seem an obvious message now; in the late 19th century, delighting in industrial expansion, it may have been less so.

Too, for a Victorian novel, the book offers a startling reversal of typical Victorian gender roles, with Nycteris, not Photogen, doing the initial rescuing. Admittedly, even in rescuing, she retains the ideals of a Victorian heroine: she is beautiful, nurturing, and comforting, not the fighter and hunter that the manly Photogen is. But for all that, she is braver than Photogen, and she is the one to persuade him to step beyond his fears of the night. All leading to a lovely, satisfying fairy tale—and, one, I am thankful to say, without the smallest touch of MacDonald’s poetry.

Versions of both the original serial and the later novel are available at Gutenberg.org and other sites.

Mari Ness confesses that mornings sometimes make her wish that she, too, could live only at night. She lives, in both day and night, in central Florida.